What does it mean to live in a listed building? And is there such a thing as common listed building problems?

There are currently around half a million buildings on the National Heritage List for England (NHLE). There

‘Listing’ a building marks the structure’s special architectural and historic interest. It introduces rigorous planning restrictions to safeguard the building’s future.

So, when you own a listed building, you are literally the custodian of a piece of British history.

Of course, these unique and characterful heritage homes come with their own problems. Traditional construction techniques from way back do not always stand up in today’s world. The sheer age of these buildings makes them vulnerable to deterioration and decay.

Ongoing repair and maintenance is a constant requirement, and the responsibility to preserve the listed building in the condition you found it in when you bought it is yours.

Here are 4 common building issues you might encounter, and what you should do about them.

1) Damp and moisture

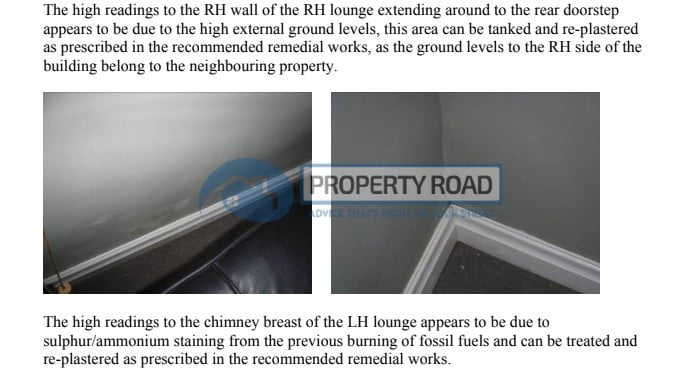

While damp is a real threat to listed buildings and their inhabitants, it is almost inevitable that

The cause could be a leak, condensation or rising damp. It’s important to look out for signs as damp is closely associated with various respiratory problems like asthma, bronchitis, allergic rhinitis, and even eczema (Mendel et al., 2011).

Fortunately, damp issues in period buildings can often be resolved relatively easily. At least once the exact root cause has been established, through a specialist damp surveyor.

In many cases, remedying the damp problem will involve the repair and replacement of roof timbers or tiles. In other cases, it will involve cleaning out, fixing and adjusting the guttering; or removing non-porous materials such as cement and concrete that prevent old building elements from breathing.

Occasionally, adjustments may need to be made to the outside, since your home’s damp proof course, where it exists, may have failed and allowed moisture to rise up from the ground into the walls.

While we haven’t owned a listed building, our current home is very old and we’ve been battling against damp and moisture issues since we moved in.

We had a specialist damp survey done as part of our due diligence before we purchased the property so we had a good idea what we were getting ourselves into. It also gave us some clear places to focus our attention and suggested remedial action which has been invaluable.

2) Thermal insulation

Improving the heat retention in your listed period home in order to lower your energy bills is not as straightforward as it may seem. Modern homeowners would add another layer of loft insulation, double glazing or even triple glazed windows for better insulation.

But adding wall insulation to a listed building may prevent the house from ‘breathing’ and cause trapped moisture and, ultimately, damp.

Aside from this, having an improved and more effective insulation in place can promote wellness. In fact, residents in well-insulated homes reported a significant improvement in health with fewer hospital visits and missed school and work days (Howden-Chapman et al., 2006).

Most period properties have solid masonry walls or

Historic England has produced some useful technical guides for energy efficiency and historic buildings that are well worth a closer look. You should also speak to your local Conservation Officer or a listed building surveyor to obtain specialist advice for your particular building.

To solve this common listed building problem in our home, we started by adding more loft insulation to take it up to 300mm (more in some places). Stick to using standard loft insulation materials though, for now it’s not worth risking the new spray foam insulation options.

We would have liked to have also installed solid wall insulation too. Unfortunately, external wall insulation is difficult as our roof lacks much of an overhang to accommodate the extra wall depth. We looked at internal insulation instead but decided against it due to the amount of room space we would lose.

Instead, we opted to improve our efficiency by installing a heat pump to replace our oil boiler, upgrading our blinds to energy efficient honeycomb blinds, and replacing our double glazing with triple glazing as and when each window fails.

This might not have given as good a result as installing wall insulation, but it’s still made a difference without the risks and upheaval that come with wall insulation.

3) Timber frames

If you are lucky enough to live in a

In contrast to infill walls, timber frames are not as strong or flexible. However, if they are well-maintained, they are found to have better shock absorption and fare better during earthquakes than the former (Poletti & Vasconcelos, 2014).

Poorly planned or executed structural changes to the building can negatively affect the timbers. This is particularly true of the hidden ones under the floor or behind rendered walls. Damp, decay and rot, as well as distortion due to excessive load bearing, can be the result.

Basic maintenance should start with cleaning your feature beams with a damp cloth or soft brush. Don’t use harsh cleaning agents which will strip away the delicate patina.

Protect with linseed oil or beeswax polish. For signs and symptoms that could indicate problems, such as soft areas of wood or light coloured insect

4) Unauthorised alterations

The act of ‘listing’ a building places it under special scrutiny and restrictions when it comes to planning consent.

In order to preserve the nation’s architectural heritage, any proposed building works on a listed building, including regular repair and maintenance, must be approved by the local Conservation Officer.

Not bothering to obtain Listed Building Consent and carrying on regardless can have severe penalties, as the owner of a

What’s more, the building owner is also liable for any changes made to the listed property before his ownership. If Listed Building Consent was not obtained at the time, it may be up to you to implement any corrections, especially since there is no time limit on these corrections being enforced.

It’s not an impossible feat as seen in the subject of Rodrigues’ and Kacel’s 2013 study. After approval, the Grade II home within the Royal Standard House was able to slash its energy consumption by 50% with no change to the facade and minimal alterations on the interiors.

This is one of those common listed building problems that you need to be aware of before you buy, otherwise it could become costly.